When the damages aren't what you'd find in a standard property inspection.

By Hadley Mendelsohn Published: Aug 03, 2022 4:32 PM EDT Save ArticleThe full interview with Eric Goldman is featured in season 2, episode 2 of House Beautiful’s haunted house podcast, Dark House. Listen to the episode here.

While state disclosure laws vary widely state-to-state, there are certain things most people agree should be standard practice when selling a home: You must disclose whether lead-based paint is present on any property constructed before 1978, for example, and some level of information around repair history is a common disclosure across states, as is obvious physical damage that can potentially become hazardous. But what about when something bad happens on a property that doesn't leave a physical trace?

In real estate terminology, a stigmatized property is defined as a property whose character or condition has been altered and thus runs the risk of being rejected by tenants and buyers who deem it psychologically or emotionally defective. The most common stigmatizing events are murder, violent crime, or death. So whether or not someone believes in ghosts or trapped energy in any literal sense, bad vibes matter, and a property can be haunted by a bad reputation. And such properties may be legally obligated to disclose that reputation, depending on a few factors.

The fact that laws have been enacted to address the issue of stigmatized properties and how they should be handled suggests that the public does care about the reputation of a property. So, we spoke with law scholar and professor Eric Goldman of Santa Clara University to unpack the concept a little further. Learn more about the field of stigmatized properties as well as disclosure laws below.

431 Hillside Avenue in Westfield, New Jersey was the 19-room mansion of John List, who was charged with the mass murder of his entire family in 1971.

Residential disclosure laws are a very complicated area of the law—perhaps because they vary so greatly state-to-state. In some states, the seller is obligated to disclose the information, regardless of whether the buyer ever asks—and even if there was a property inspection. For example, in Alaska, the listing agent "must disclose any known murders or suicides in the last year. In the event the agent is unaware, they are not liable." In Maine, meanwhile, "an agent would need written permission from the seller to disclose the information to a buyer should they inquire," and in Montana, state law "prohibits suicides or felonies from being disclosed by an agent," according to Spaulding Decon, a decontamination service offering crime scene, hoarding, and meth-lab cleanup. Indeed, state disclosure laws often contradict each other.

"I think it's actually a reflection of the tortured nature of the opinions" that come up in stigmatized property cases, Goldman muses. "Judges don't always agree on what needs to be disclosed. And state legislatures have passed laws saying there are times you must disclose, or there are times when you're not obligated to disclose, and those laws aren't harmonized either. So the reality is that these are simple questions, what must a seller or tell, and when, and yet the answers differ wildly across jurisdictions and across the particular type of fact that might need to be disclosed."

Even in the strictest disclosure law state, California, there are parameters. After three years, the death doesn't need to be disclosed. "There has to be some cutoff somewhere, right? There has to just be a basis to say, you know, [as a seller] I'm not responsible for the fact that homes have been around for 150 years and people have surely died in there," says Goldman.

It's important to understand the difference between patent and latent defects when unpacking disclosure laws. "Patent defects are the [physical] things that should show up in a standard property inspection," Goldman explains. A property inspector visits the home, and writes up a report that calls out any potential problems with the property. Most buyers opt for a property inspection, but they can choose to waive the property inspection, and if they close on a sale anything that was disclosed prior is now their responsibility as the new owners.

Sometimes, the seller will actually run the inspection themselves. "Here in California, where we have a pretty hot real estate market, it's actually not uncommon for a seller to do the property inspection and to provide that to all of the potential buyers before they place their bids as a way to expedite the process and to remove some of the potential contingencies that a buyer might include in an offer," Goldman notes.

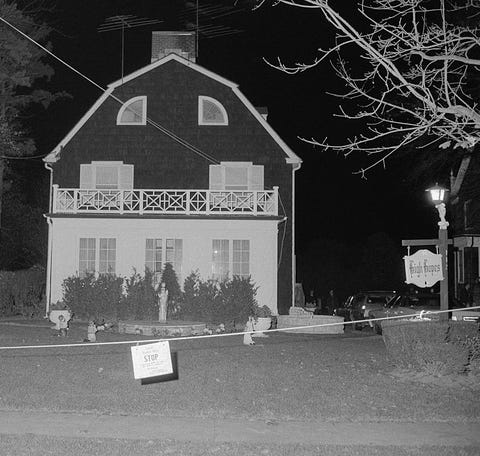

The Long Island home of the DeFeo family, also known as the Amityville Horror House, has become the source material for many haunted house films, books, series, and podcasts.

Latent defects, on the other hand, are things that "a property inspector might not find in the course of doing their ordinary diligence. But if the seller knows about the latent defects that the property instructor can't find and which the buyer wouldn't see, they might be required to disclose those affirmatively," Goldman adds.

Why do latent defects matter? Nonphysical issues might still affect a buyer's willingness to buy a property, plain and simple. In the context of a murder, the seller may know that the buyer isn't aware of this event, but that if they were aware, they may consider it a material condition of the home.

A ghost haunting the property is a stigma that might impact a property, but it's more difficult to prove than a factual event like an on-site death or murder. As such, it's rare for a property to be recognized as stigmatized due to perceived paranormal activity in a legal context because it's more difficult to procure reliable and credible evidence that could be introduced in court, Goldman explains. Of course, there are exceptions," like in the Stambovsky vs. Ackley case, when the judge was trying to come up with an equitable solution based upon a very specific set of circumstances.

Interestingly, sometimes the inverse is true in that a stigmatized property could actually be worth more because of its dark history. Marketing a home as a haunted "can attract a small, but potentially very lucrative market," says Goldman. But there are also some tricky disclosure laws that make that complicated, too. If a broker did want to market the house as haunted, they will also have to be able to document the phenomenon, or not over-promise the haunted nature of the home. "I don't think most brokers are going to be confident making that type of disclosure since they can't guarantee the ghosts are still going be there and they can't really verify the past behavior." Instead, they would need to frame it in a way that's more speculative or provided a qualified disclosure.

Journalists gather outside the Beverly Hills home of Paul Bern and Jean Harlow as they await further news after the body of Bern had been discovered by his butler.

"If the house was advertised as haunted and that became part of the deal and then, in fact, it's not haunted, that's just straight out false advertising or fraud or, a misrepresentation of the property's value, and condition," Goldman says. "There's a series of legal doctrines that would provide recourse for the buyer under those circumstances. That's one of the reasons why brokers are not likely to say that a house is haunted because they don't want to put their professional reputation and finances behind a statement that they don't necessarily believe that they can validate."

Real estate disclosure laws are clearly very complicated and difficult to navigate for both buyers and sellers, whether the property is "stigmatized" or not. We asked Goldman to share his best advice for all parties involved. Here are his five key tips:

Curious to hear more in-depth ghost stories about stigmatized properties as well as disclosure advice from Eric Goldman? Listen to Dark House.